Local Opinion: Attitudes To Migration As A Test For East & West Within EU

- 18 Sep 2017 8:48 AM

Without mentioning Hungary by name, Mrs Merkel said there was one government in Europe which rejects the ruling by the European Court on compulsory refugee relocation quotas. She deemed that stand ‘unacceptable’.

Heti Válasz’s Bálint Ablonczy admits that in their first reactions, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Justice did produce what he calls ‘rhetorical fireworks’ in their criticism of the verdict. He adds, however, that Prime Minister Victor Orbán mentioned soon afterwards that he had ‘taken note’ of the ruling. ‘As members of the European Union we can hardly show disrespect for the law on which is it is based’.

The Prime Minister continued however, that he didn’t intend to change his migration policies. Ablonczy predicts that Hungary will lose a second trial in the European Court if she is sued by the European Commission for not complying with the quota system which has now been accepted as legal by the judges in Strasbourg.

Nevertheless, he continues, European diplomats are working on a compromise which would allow those countries with few asylum-seekers to express their solidarity towards those countries with an excessive number, in flexible ways.

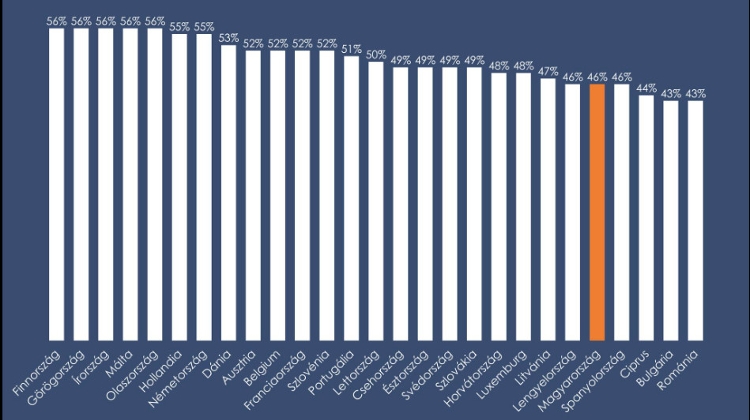

According to this new system, the protection of Europe’s outer borders as well as financial contributions could also be accepted as expressions of solidarity. Under this scheme, refusing to accept its share of asylum seekers would cost Hungary €48 million, which amounts to approximately 1% of the net subsidy transferred yearly by the European Union to Hungary. Meanwhile officially, Hungary is still ’at war’, and the question Ablonczy asks, is for how long.

In Demokrata, Gábor Bencsik praises the attitude of the Hungarian government as expressing the conviction that Europe is threatened by an ‘exchange of populations’. Over the past 5000 years, he explains, nations have constantly surfaced and been submerged, and European leaders are wrong to think that their present societies are automatically there to stay forever.

Europe, and within it, Hungary are not threatened by military aggression, but by demographic problems, Bencsik argues. While Europeans ‘have lost their reproductive capability’, other peoples are unloading their demographic surpluses on Europe. ‘Only the most dumb observers believe that an exchange of populations will not produce an exchange of cultures as well’, Bencsik goes on.

His recipe is twofold. On the one hand, he suggests a variety of measures encouraging people to have more children, from new forms of tax relief to family friendly workplaces. On the other hand, the authorities must by all means prevent the inflow of new populations.

Which implies that they have to resist political pressures from forces which ‘out of dumb naivete or profiteering’ want ‘the dams to be pulled down and the flood to be let in’. Bencsik suspects that some European countries have already passed the tipping point and would not be able to turn back on the road towards population exchange even if they realised that they have been wrong so far. And still, he warns in his concluding sentence, ‘it is in our joint interest to prevent the rest from following suit’.

In Élet és Irodalom, Botond Bőtös believes that the unity of the Visegrád 4 over the refugee issue is being progressively undermined by diverging interests and visions between Hungary and Poland on the one hand and the Czech Republic and Slovakia on the other. Central Europe is at an historic crossroads, he writes, as the leaders of Germany and France push for an expanded and more integrated Eurozone.

He sees the diplomatic events of the past few years as signs that the Czech Republic and Slovakia intend to move closer to the West than to their Hungarian and Polish neighbours. They have been a lot milder in their rejection of the quota system, although that rejection reflects the views of most Czechs and Slovaks.

They have also engaged in a new cooperation scheme with Austria under an agreement signed at Slavkov this summer, which Bőtös interprets as proof that they intend to dissociate themselves from what he terms the authoritarian tendencies of Poland and Hungary. Austria’s entry into the central European equation reminds Bőtös of the last decades of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

At that time, he reminds his readers, Budapest resisted Vienna’s endeavours for a more federalist system in which Hungary would have lost her primacy among the (non Austrian) nations of the Empire. Hungarians and Poles, the analyst suggests, are more inclined to be jealous of their newly returned sovereignty, which may be one of the reasons why they oppose unifying efforts by Brussels.

Bőtös is convinced however, that increasingly intensive cooperation within the European Union as envisaged by France and Germany is unstoppable and predicts that Hungary ‘will be left out in the cold.’

Source: BudaPost

This opinion does not necessarily represent the views of this portal. Your opinion articles are welcome too, for review before possible publication, via info@xpatloop.com

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs