Xpat Opinion: Top 5 Fallacies In The ‘Free But Not Fair’ Story In Hungary

- 3 Apr 2014 9:00 AM

Hungary elects a new Parliament this Sunday, April 6, under a new system introduced in 2011. Frequent readers of my blog know that I have written regularly about the new electoral system, on its details and how it came about. (See the 9-part series of posts on the system here).

But its time to address this particular line of criticism head on. The claim, a story that detractors like to use especially in international circles, is designed to undermine the legitimacy of the results of Sunday’s voting. Repeated often enough, it begins to take on a momentum of its own. But, as always, such claims should be challenged. What are the facts? How exactly will the elections not be fair?

Here are a few of the common fallacies and why they just don’t hold water.

5. The reason the Government changed the electoral system was to ensure another victory for the governing parties.

In fact, there’s been a broad consensus on both the left and right for quite some time that the law needed to be changed. The old system elected a Parliament way too big for the country’s size. It was outdated in many respects and the inequality of constituencies was much greater – resulting in an inequality of votes. The Hungarian Constitutional Court, Venice Commission, and OSCE have all proposed changes in the past 20 years. But prior to the current government only one other government had the necessary majority to make changes and nobody mustered the political will for reform. Out of the 23 recommendations OSCE made in 2010, 15 are fully and 2 are partly incorporated in the new legislation.

As a result, the size of the Parliament will shrink to 199 from 386. Out of that total, 106 will be decided in single mandate electoral districts – a larger portion than before – and winning in those districts will become more important compared to the former system in which party lists had a greater significance.

Read more:

Why and how the system was changed

The OSCE Notes on the Hungarian Election System

4. The opposition was not consulted in drafting the new election legislation and constituencies.

Yes, they were. The opposition was invited to consult during the drafting of the law. But they decided to boycott. It’s a little cynical to refuse to take part in discussions and then later cry, “Unfair!”

Despite that, a seven month-long debate on the draft legislation did take place in parliament. And some elements of the law in fact come from opposition initiatives, like making the candidacy process easier. That was initiated by LMP, the green opposition party. As a result, LMP now has one candidate in every constituency this time, which they struggled to do in 2010. There are many new and reborn parties – the Smallholders are back, for example – competing for the votes of what polls say is still a high number of undecided voters. The ballot will also have a Roma party, something the Roma minority has struggled to achieve since 1990.

But, that’s not all. Hungary’s own Constitutional Court ruled that no more elections could be held based on the old constituencies.

In 2005, the Constitutional Court ruled that the electoral constituencies must be changed and gave a deadline. They would have to be changed by June 30, 2007. But nothing happened. In 2009, a group called Political Capital – a private consulting firm and think tank – initiated a proceeding before the Court, complaining that the constituencies had not been changed. Thus, in 2010, the Court formally annulled the 1989 order of the Council of Ministers of the People’s Republic – the communist-era government – that set out the constituencies that had been used since 1990.

By law, the old constituencies no longer existed! New electoral districts had to be drawn and be more proportional in size. The governing party alliance had the authority from the voters to carry that out, and they did so according to international best practice and recommendations of the OSCE and Venice Commission. The opposition boycotted the consultations.

Gerrymandering? I’ll respond to that one below.

Read more:

What You Should Know about the New Electoral Districts

Getting Your Name on the Ballot is Now Easier

Guess Who Doesn’t Want International Election Observers

The OSCE Notes on the Hungarian Election System

3. Legal limits on campaign ads mean that parties can’t place their ads on non-public TV and radio and billboards. The government under the new system is now able to influence the race with ads.

No. Campaign ads on TV and radio are limited in a way to ensure equality, taking practices from the British and the French systems. Smaller parties are now able to get just as much airtime as the bigger players, free of charge. The state-owned public media must provide the same airtime for all of the 18 parties competing on the ballot as well as the 13 minority parties. Commercial media, meanwhile, can choose whether they will run the ads, but have to provide the same equal airtime. Parties can buy billboard space just like before, except that one form of billboard ad (posters hanging on the side of the roads) was banned years ago for safety reasons.

Read more:

Leveling the Playing Field for Campaign Ads

Journalism Lite at the New York Times

The OSCE on the Hungarian Election System – Pluralistic Media

2. The new system has spawned many Potemkin parties to distract voters, and these parties have cheated in collecting nominations

In 2014, 18 parties have qualified for the ballot with a nationwide list, but the highest number was in 1994 when we had 19 parties competing. That means there is more choice. It has made it easier for some old parties – like the Independent Small Holders’ Party, the Social Democratic Party, or the Worker’s Party – as well as new parties of long-time political figures – like the party of Kalalin Szili or that of Mária Seres – to get on the ballot and contest the election. A few of the new ones are openly laying the groundwork for running again in 2018.

The rules on collecting nomination signatures were revised based on an initiative from one of the opposition parties, LMP. According to the new rules, parties have to show support of only 500 voters, instead of 750 of the old recommendation slips. Constituencies are larger and one voter can support multiple candidates or parties. The OSCE writes in its report that all the political parties they met welcomed the changes.

Did some parties cheat with the signatures? We don’t know yet. That’s up to the police to investigate as this is a serious crime.

Read more:

The OSCE Recommended Lowering the Bar for Candidates to Get on the Ballot

Getting Your Name on the Ballot is Now Easier

Greater Choice in 2014

The OSCE Notes on the Hungarian Election System

1. The new constituencies are gerrymandered for Fidesz so the ruling parties can win with less than 50 percent of the vote

This is one of the most common charges. Yet, has anyone bothered to take a good, hard look?

To gerrymander a district is to draw it in a way that gives one political party an advantage. And how is it drawn, based on what? Based on voting history.

That’s where it becomes very, very difficult to show gerrymandering with the new districts. Voting preferences in Hungary have changed dramatically. In 2010, two parties, the Free Democrats and the Hungarian Democratic Forum, which had been in parliament since 1990 and had served in different government coalitions failed to meet even the five percent threshold, fell out of parliament and now no longer exist. Two, new parties, Jobbik and LMP, were elected to parliament. The Hungarian Socialist Party, which had been one of the most powerful parties of the left in all of the CEE region, lost one million of its voters. Some districts that had always been red, voted for Fidesz. Out of 176 constituencies, Fidesz-KDNP won 173 in 2010.

How would you gerrymander the districts on a political landscape that has changed so much?

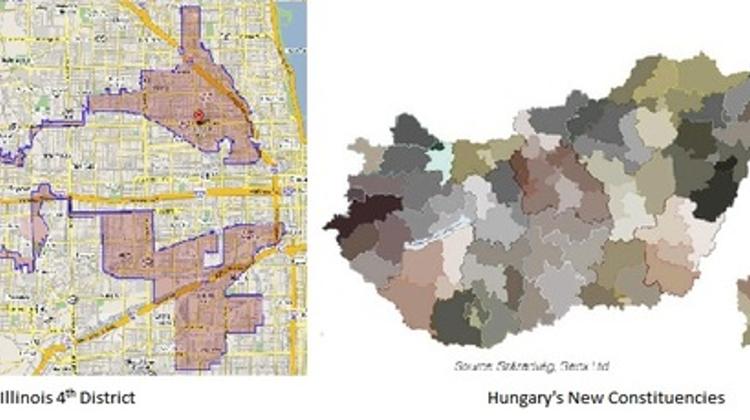

Secondly, what does gerrymandering look like? Have a look at this district in the state of Illinois, the 4th district. In Hungary, the law explicitly says that districts must be territorially integrated and remain within existing county borders. They must have a more equal number of voters. There’s a coherence to the new boundaries.

It is true that any party can capture a majority of the seats with less than 50 percent of the votes, but those, who claim that this is a problem make the mistake of confusing a two-party, majoritarian system, like in the U.S., with the multi-party, mixed system that we have in Hungary. As I wrote in my previous post, it’s all about winning the districts. Here’s an example.

If a governing party candidate wins a district with, let’s say 40 percent, the candidate of the MSZP-led alliance gets 30 percent, Jobbik wins 15 percent, LMP takes 5 percent and other candidates share the remaining 10 percent, then the seat goes to Fidesz in the Parliament. If that happens in many districts – Fidesz-KDNP won 173 of what was then 176 districts (!) in 2010 – then the party can reach a significant majority. You see how it works.

Read more:

What You Should Know about the New Electoral Districts

The Princeton Professor Fails Electoral Math

The OSCE Notes on the Hungarian Election System

Reasons to be Careful with Election Forecasts

By Ferenc Kumin

Source: A Blog About Hungary

This opinion does not necessarily represent the views of this portal. Your opinion articles are welcome too, for review before possible publication, via info@xpatloop.com

LATEST NEWS IN current affairs