'An Englishwoman's Life in Communist Hungary': Chapter 5, Part 7.

- 5 Jul 2023 6:53 AM

Now You See It, Now You Don’t and House of Cards have been included as part of the Open Society Archive dedicated to this period in the CEU. You can read a serialisation of them here on Xpatloop. You can also buy the dual-volume book on Kindle as well as in Stanfords London.

Chapter Five: Children and Change

Part 7 – End of an era

By February our thoughts were more focused on the imminent birth of our second child. She - if indeed it was to be a girl - was due on the 13th and I somehow hoped it might be the 14th, St. Valentine's day.

We had arranged with Cili next door that she would take care of John when Paul went into the hospital with me. The 14th came and went, and the following day I had to go for a check-up.

‘Absolutely no sign of this baby being born yet,’ my doctor pronounced, ‘It could be another week or two. Come back the day after tomorrow and I'll see you again.’

I was in no particular hurry, especially now that John - and we - were at last sleeping through most nights, and I knew that the baby would put an end to that. I had also received a parcel of one hundred and fifty advanced level translations to mark, and I wanted to finish them.

Late in the evening I was still marking and Paul listening to some music on the radio. I began to feel an aching in my back and a general sensation of discomfort. It was eleven o'clock, so I decided to have a warm bath and go to sleep. As I got into bed Paul came in to get something from his desk.

‘Well, who knows, tomorrow may be the day,’ he said.

‘Could well be,’ I answered, ‘I feel a bit odd.’

‘What do you mean? Shouldn't we go to the hospital?’ asked Paul in more urgent tones.

‘No chance,’ I replied turning over, ‘I want a good night's sleep.’

‘Oh, no you don't!’ he retorted. ‘John's birth wasn't exactly textbook, you might easily have had him at home, and second babies are usually quicker. No, we're going, even if they just send us home again - I'm not delivering it here!’

‘Don't worry, Cili would know what to do,’ I said yawning and lazily pulling up the covers.

But it was too late. Panic had set in and Paul was already on his way to ask Cili to come and sleep in our flat to look after John. I groaned and got out of bed. Paul arrived back with Cili who looked suitably excited.

‘Have you had any contractions?’ she asked.

‘No,’ I replied, ‘but my back aches. You really needn't stay, I'm sure they'll send me home again.’

I got dressed, and together we walked around the block to the hospital entrance. The night duty doctor was duly awoken and summoned, and I was taken off to be examined.

‘The cervix is six centimetres open,’ he said, ‘you'll have to stay here.’

‘But I'm not having any contractions, surely I can go home for tonight, I only live on the corner,’ I protested.

Paul was not keen on this idea, and I was thus persuaded to remain in the labour room while the nurse promised to ring him if anything happened. It was a long night. Women came, had their babies, and went.

Every hour or so a nurse came and attached me to a machine designed to monitor contractions, but the result was the same - nothing. I felt exhausted.

Some time before eight o'clock the following morning my doctor arrived. Having seen me less then twenty-four hours previously, he looked somewhat surprised.

Looking at my notes he said, ‘Well, we'll have to wait and see what happens.’

‘But can't you do something?’ I asked, ‘I can't just lie around here for days waiting.’

He considered. ‘We could break the waters if you like,’ he volunteered.

‘Anything,’ I said.

Thus, at nine-thirty the waters were broken, Paul summoned, and Hannah born shortly before eleven o’clock. She proved to be the opposite of her brother: I was not to see her with her eyes open in the five days of our stay, nor was I able to wake her to feed her.

She was, nevertheless, healthy and beautiful, and to our great relief she slept regularly for three and four hours, day and night, for three months, with hardly a single cry.

Hannah

Yet, even in the midst of life with a newborn baby it was impossible to remain isolated from life outside.

Just in February itself, the ruling Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party decided to accept a multi-party system and also declared the 1956 revolution (always officially referred to as a counter-revolution), to be a popular uprising.

I wondered what Miklós would make of it all - he was now in Bloomington, Indiana, and would not return until the summer. His letters were more concerned with his ability to overcome the culture gap he felt in America, and his lack of adequate finances.

We too became infected with the atmosphere of anticipation and excitement. It was now almost seven years since we had arrived in Hungary, intending at that time to stay for just one, or maybe two years.

Since then we had renewed our residents' permits every summer, but the birth of the children had put a time limit on our stay. We had decided they should go to school in England and avoid the inevitable Marxist-Leninist teaching combined with compulsory Russian lessons, which left almost everyone we knew unable to ask for a cup of coffee after eight or more years' instruction.

We also did not relish the prospect of flat-hunting again, and Ági and Kazi would be returning in the summer for good.

Many of our conversations during walks in the City Park were concentrated on the various possibilities for our future. Laurence's mother had offered to look for suitable jobs for Paul in the newspaper, but somehow the urgency of the situation seemed to be diminishing with each new development in Hungary's history.

On one such walk, we found ourselves behind the rostrum on Dózsa György út where the party officials would stand on such occasions as the May Day parade. We suddenly noticed that a black star had been sprayed on the edifice, with the word Beware! underneath.

There was a policeman standing on guard next to the structure, and nearby we also saw that the statue of Lenin had been shrouded in swathes of plastic sheeting. Not many weeks later the statue was silently, and unceremoniously, removed.

Back in our flat we found ourselves watching the removal of something else: the Chimneysweep restaurant. Its crumbling walls were being demolished, the green trelliswork a pile of splintered timber among the broken tiles and dust-covered bricks.

It was June; an announcement was made that Russian was no longer to be a compulsory subject at school. But what was greeted with unbelieving enthusiasm was the news that Imre Nagy was to be reburied at a huge ceremony at which all those executed after '56 would also be commemorated.

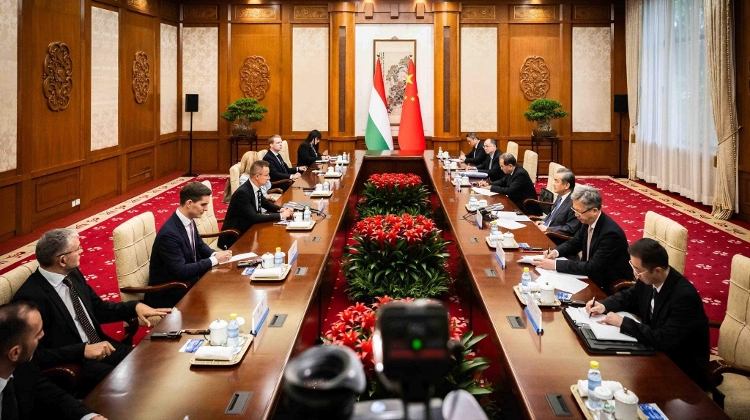

Now, on our walks in the park we watched as the facades of the two art galleries and the pillars of Heroes' Square were draped in black cloth.

The art gallery’s pillars draped in black Courtesy Fortepan/ tm

We thought back to Miklós's first visit to England in 1979 when he had acquired a book about Imre Nagy in London, a thick tome he had read from cover to cover but did not risk taking back to Hungary in his suitcase.

The date, 1956, and the name Imre Nagy could then only be whispered among friends. Now, booklets were being printed with the list of names of all those who had been sentenced to death, and June 16th - the anniversary of Nagy's execution - was named as the day for the commemoration.

There was no doubt in anyone's mind that this was the final step, the point of no return. The tempo of change had been accelerating, every aspect of life felt as though it were in a state of flux, stability was being swept away and we were being swept along with it.

*

I was awoken by Hannah in the cold hours before dawn on the 16th. I walked over to the window gently rocking her to sleep. Outside, the night was still dark and starry.

Below me lay the empty space that had been the Chimneysweep, a few bricks and windblown newspapers all that remained. Just beyond lay Heroes' Square, shrouded in black, awaiting the momentous day which lay ahead, and not much further away was Garay tér, the cats fed and sleeping on the roofs of the silent market.

Only at Rákóczi tér some girls would be waiting on the corner, while the all-night tram occasionally rumbled its way past.

The whole city, the whole country, was slumbering its last, unknowing, dreamless and innocent sleep.

***

Budapest by night

END OF BOOK ONE

Book Two will be serialised from September

Click here for earlier extracts

Main photo: A statue of Lenin is removed

LATEST NEWS IN community & culture